Aside from the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus, and the early years of the Christian movement described in the New Testament, the Protestant Reformation of the 16th century is the most important event of Christian history, and it shapes our lives as Christians right down to this day. The beginning of the Reformation is usually dated to October 31, 1517, when Martin Luther nailed his “95 Theses” on the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg, Germany. We’re going to celebrate the 500th anniversary of that event this October, but before we get there I want to look back a little deeper in history to the roots of the Reformation.

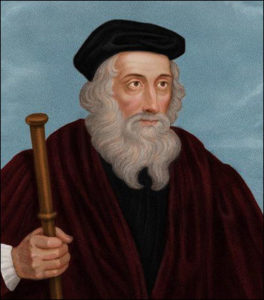

John Wycliffe has been called “The Morning Star” of the Reformation. He was an Englishman, born in 1320, about two hundred years before Luther’s 95 Theses. At that time, what passed for Christianity among the common people was a hodge-podge of superstition and folk religion. Even most priests did not read or know the Bible. Copies were rare, in Latin, and largely a mystery to common people. The influence of the Church was pervasive in every aspect of life, but what was taught and believed bore little connection to the Bible. When people went to church, which nearly everyone did, they did not hear sermons based on Scripture. Sermons consisted of miracle stories – not biblical miracles, but legends about various saints of the Church spun together with folk superstition, Church dogma, and moralism. People were taught that God would judge them by their works, and their only way to heaven was to be diligent in doing everything the Church told them.

Wycliffe was a scholar and professor at Oxford University. He devoted himself to the study of the Bible and it revolutionized his life. He came to believe the Church had lost its way, and he devoted himself to teaching the Bible and translating it into the language of the common people. He was the most popular teacher at Oxford and his lectures were usually packed. He began to travel around England, teaching where he was allowed.

He spoke out against the veneration of saints and praying to saints, saying that it had no foundation in Scripture and that Jesus Christ is the only Mediator we need to come to God. He said the only thing needed to please God was faith in Christ, not observing the sacraments or pilgrimages or penance or anything else the Church prescribed. He rejected the notion of purgatory and paying “indulgences” to get out of it, because it was nowhere in the Bible, and the only way to heaven is not purgatory but faith in Christ. He said it was useless superstition to say masses for the dead. He rejected the idea that monks and nuns were holier than anyone else because the Bible says every believer is made holy by faith in Jesus Christ alone. He rejected the authority of the Pope, and even the idea of the papacy, because it’s not found in the Bible. He said priests could get married because, you guessed it, the Bible holds up marriage as a holy thing. He spoke out against the wealth and luxury of Church officials, saying it bore no relation to Jesus who had no place to lay his head.

Wycliffe taught the biblical idea of predestination, that God elects (chooses) those who will be saved. You may ask, what’s revolutionary about that? You see, if God chooses who will come to him, that means the Church does not. The Church at that time taught that the only way to heaven was through the Church, and faithfully jumping through all the hoops the Church required. But Wycliffe was more persuaded by Romans 1:17: “… the righteousness of God is revealed from faith for faith, as it is written, ‘The righteous shall live by faith.’” In other words, the only way to be saved, to be right with God, was through faith in Jesus Christ alone. Wycliffe said, “Trust wholly in Christ; rely altogether on his sufferings; beware of seeking to be justified in any other way than by his righteousness.”

Wycliffe came to believe the Scripture alone was the authority for the Christian life, not the hierarchy of the Church. He taught that every Christian should learn to read the Bible, and that it should be translated for the common people. He and some of his allies translated the Bible into English and distributed hand-copied manuscripts as widely as they could. One Church official said: “By this translation, the Scriptures have become vulgar, and they are more available to [common people] – and even women who can read – than they are to learned scholars, who have a high intelligence. So, the pearl of the gospel is scattered and trodden underfoot by swine.”

Church officials bitterly opposed Wycliffe and tried to silence him. But he managed to stay one step ahead of them, and in 1384 he died peacefully at age 64. But Rome found they couldn’t stamp out the spiritual awakening he has started. In 1428, forty-four years after his death, they dug up his bones, burned them, and threw the ashes into the River Swift. It didn’t work. His movement, known as the Lollards, never completely died out, and when the Reformation came to England over 150 years after Wycliffe’s death, the ground of spiritual awakening was already fertile and ready.

Believers today can learn much from John Wycliffe, but perhaps first and foremost is this: to treasure having a Bible in your own language and that no one can stop you from reading it – no one, that is, except you. The tragic irony of our time is that the Bible is perhaps the most revered unread book in the English language! John Wycliffe found that when he studied the Bible, he met there the living Savior, Jesus Christ. When we read with an open heart and eyes of faith, the Bible is not a dead letter, but “the Word of God . . . living and active, sharper than any two-edged sword” (Hebrews 4:12). If you hunger to know God, if you would find hope and peace in Jesus His Son, the way has not changed. Take up and read. And as you do, say a prayer of thanks for the life and ministry of John Wycliffe.

Pastor Phil Moran

One Comment

Larry wood

GreAt start Phil!